Learn

July 31st is National Avocado Day in the U.S. — a day dedicated to celebrating the wildly popular berry (yes, it is a berry — you can Google it). But rather than celebrating the invention of avocado toast (thank you, Bill Granger), I want to marvel at the weird history of avocado breeding.

Probably the most famous crop breeder is the heroic Norman Borlaug — the American agronomist who is credited with kicking off the Green Revolution. One of Borlaug’s best-known innovations was a new way of breeding wheat, known as “shuttle breeding”. In the summer he and his team bred wheat at high altitude near Mexico City; in winter they used the lower-altitude Sonoran Desert. This allowed him to squeeze in two generations of wheat a year, when other breeders produced one. By 1956, Mexico was self-sufficient in wheat production; the technique is now used around the world.

Borlaug bucked conventional wisdom, agronomic theory and endured the sniggering of local farmers. But his unorthodox approach ultimately led to varieties of wheat that were semi-dwarf (that is, shorter and stronger), high-yield, and disease-resistant. His discovery is credited with feeding hundreds of millions of people — and earned him the Nobel Prize.

Rudolph Hass is less well-known than Mr. Borlaug. Rudolph was a mail carrier in Pasadena, California and an enthusiastic amateur horticulturist. In 1926, he planted three random avocado seeds in a little orchard that he cultivated, with the hope of using them as root stock on which to graft scions of the then-popular smooth, green-skinned Fuerte avocado. Two of his three seeds failed to germinate, and his grafts failed to take on the one that did. Legend has it that Rudolph was going to chop the hapless sapling down, but instead he let it bear fruit. The bumpy black-skinned fruit looked weird, but tasted great. Even better, his funny new tree yielded more, bigger fruit, year-round, with a longer shelf life and richer flavor than the Fuerte.

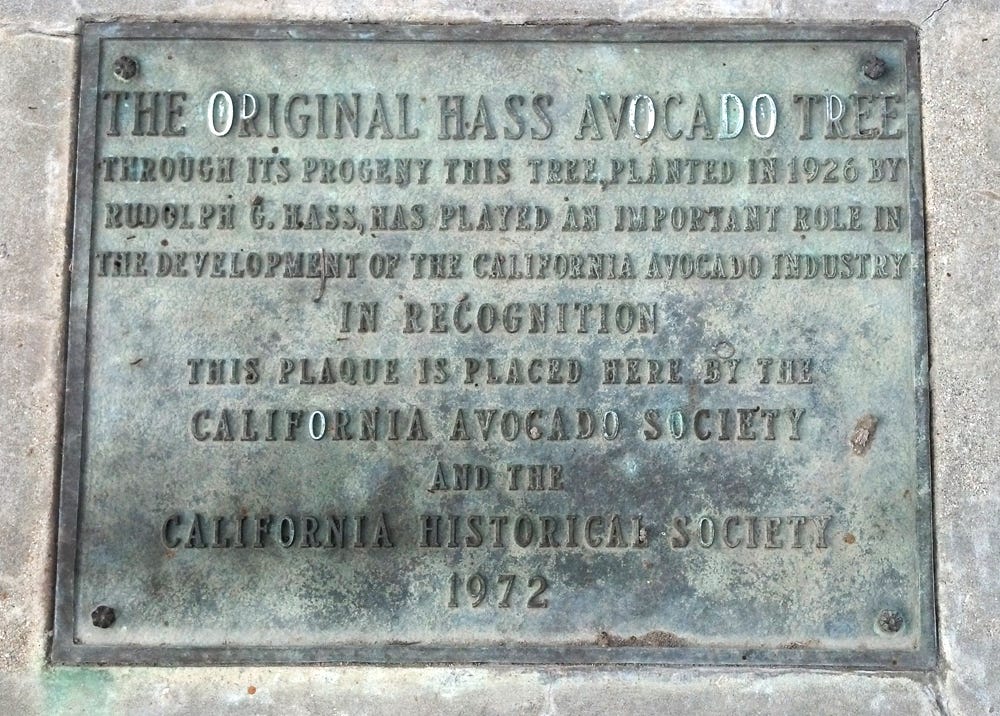

The plaque beneath the original Hass avocado tree. Photo via La Habra Heights Avocado Festival

Today grafted seedlings derived from Rudolph’s ‘mother’ tree account for 80% of the world’s $9B avocado crop. Mr. Hass didn’t make much money from his discovery, or win the Nobel, and he worked as a mail carrier until he died — but he is immortalized by giving his name to the world’s favorite avocado. Rudolph’s little orchard was soon swallowed by a housing development, but the original Hass avocado tree stood until September 2002, and is memorialized with a plaque in La Habra Heights.

Perhaps one day we’ll decode the plant genome and fully understand the role of every allele and the decillions of possible combinations. But until then, intuition, tenacity, luck, experimentation, and a healthy disrespect for the ‘right way’ of doing things will keep crop breeding exciting and surprising — and could even lead to the next world-beating discovery.

Here’s to keeping it weird on National Avocado Day!