Celebrating the Positive Potential for Robotics Through Film

Reflections on the relationship between storytelling and robotics from the 8th annual Robot Film Festival

Like many roboticists, I have a love/hate relationship with science fiction. On one hand, the stories that gripped our youthful imaginations can serve as inspiration — energizing our creative impulses and encouraging our efforts to build future technologies. On the other hand, dystopian visions can grip us in a different way, providing unsettling visions of what could one day come to pass. While most science fiction imaginings are a far cry from the reality of robotics today, they do inform how society deals with the practical and ethical implementations of new technologies and how society thinks about applying them to real problems.

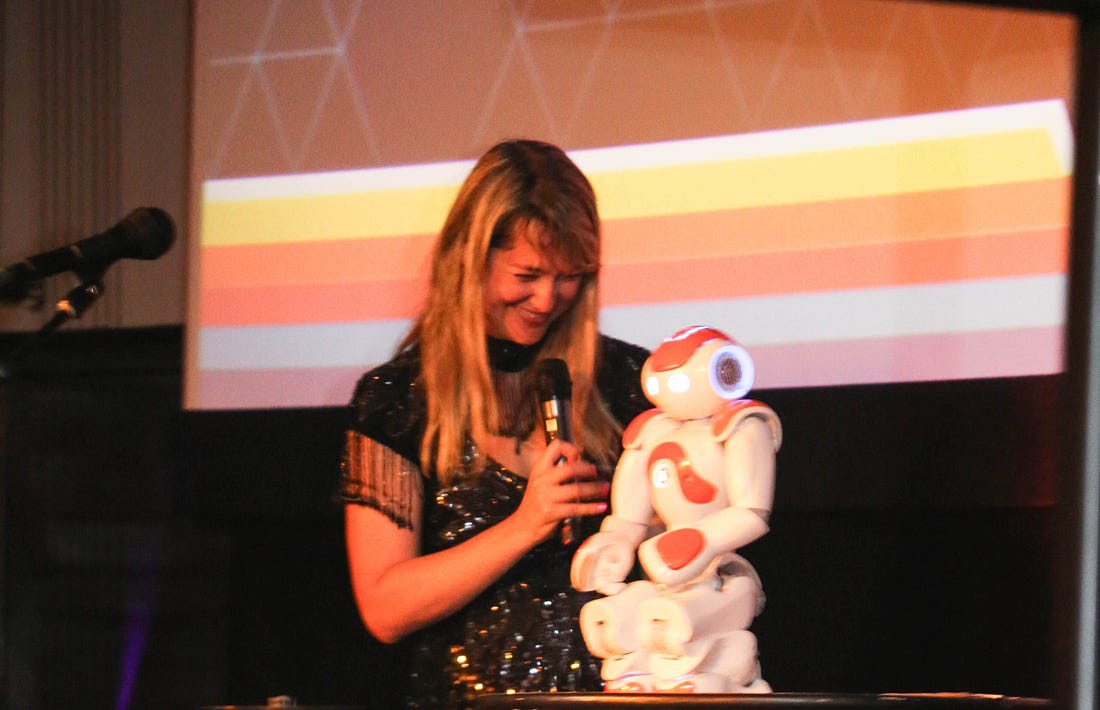

Co-founder Heather Knight banters with Ginger the Robot at the Botsker Awards Ceremony (photo credit: Liana Kramer)

As a roboticist working to advance robotic capabilities, I feel it’s important to recognize the influence of the stories we tell ourselves. That’s why, in 2011, I co-founded the Robot Film Festival with roboticist Heather Knight and producer Chrys Wu. This labor of love is designed to nurture the relationship between storytelling and robotics. By offering a forum for people to come together and share creative, scientific, and commercial perspectives on robotics, we hope to celebrate the positive potential of intelligent technologies.

Society’s understanding of robots has fascinating historical and cultural roots. The challenges of the European industrial revolution, for example, are visible in a long lineage of books and films from Frankenstein in 1818 to The Terminator in 1984. Likewise, Japanese works following World War II often grappled with human decisions around the use of technology rather than attributing judgment to the technology itself, such as the nuclear-powered Astro Boy. Drama, conflict, and adversity make for good stories, and some of Hollywood’s most compelling visions of robot-populated futures depict dystopian possibilities crafted to warn or frighten us. This pessimism is a headwind that roboticists often face in discussing our work with the broader world.

But perhaps an even greater challenge posed by science fiction to the field of robotics is high expectations. Fictional robots in movies are generally depicted as highly capable and intelligent — flawlessly engaging with people, handling objects and tools, or navigating the physical world. These cinematic imaginings are universally unrealistic, or at least unrealized in current academic or commercial realms. Although sensor technology, hardware dexterity, and computational cognition are advancing in leaps and bounds, state-of-the-art robotics still falls frustratingly short of our high expectations for what robots should be capable of doing.

Over the past eight years, Robot Film Festival events have been headlined by high-profile feature films. These include Spike Jonze’s I’m Here, a love story between two robots; Jake Schreier and Christopher Ford’s Robot & Frank, a comedy about an aging ex-burglar and his robotic caretaker; and Takahiko Akiyama’s Hinokio, a story about a wheelchair-bound student’s use of a telepresence robot. But the heart of the festival has always been the curated sessions of submitted and short films.

The 8th annual Robot Film Festival was in held at McMenamins Mission Theater in Portland on July 14, 2018

In addition to live-action and animated sci-fi films from around the world, these shorts include academic videos showing the latest research into what is possible, home videos showing pets playing with autonomous vacuum cleaners, and journalistic pieces casting an objective eye on how people are deploying robots in the world. Some of my favorites from this year’s event included The Nostalgist, a film inspired by a short story from sci-fi author (and fellow roboticist) Daniel H. Wilson, and Robot’s Delight, a music video that explains real cutting-edge human-robot interaction research as tongue-in-cheek rap. You can watch these, and check out every year’s collection, in our film archives.

Just as I strive to do with my work as a roboticist at X, through this film project I’ve been grateful to witness and encourage fruitful interactions between artists, engineers, and the viewing public. What we see informs what we imagine, and what we imagine informs how we build. The more thoughtfulness, nuance, and understanding we can bring to new technologies, the better our future will be.